The son of a wealthy Tennessee family, Pete Kreis had grown up during the time that European manufacturers dominated automobile racing at the Indianapolis 500. When he broke into big-time racing in 1925, Pete and his American compatriots were eager to demonstrate that cars and drivers from the U.S. could successfully compete against Italian, German, and French roadsters.

Pete quickly became known for his track speed as he drove a Duesenberg to eighth place in the Memorial Day Classic at Indianapolis in his rookie season. He was delighted when he was chosen by the team to travel to Italy to test his car against the best that the Europeans could offer. He gladly packed up his roadster and prepared for competition in the Grand Prix near Milan.

Although the season was only half over, Pete had quickly made a name for himself. He had shed his youthful shyness, and his newly adopted bonhomie gave him the ability to make friends easily. His personality, however, was not what attracted attention to the young driver.

When racing veterans saw him on the track, they quickly learned that the boy could fly. Speed—that’s what attracted the race crowd to Pete. The veterans watched, and they knew. People like Tommy Milton, the first two-time winner at Indy; Harry Miller, the mechanical genius; and Harry Hartz, an early convert to the Millers and one of the few who later would make the difficult transition from driving a car to managing a team. Like the Duesenberg brothers, these men had witnessed Pete’s ability to reach the sustained speed needed to win on the fastest tracks.

The young driver’s growing reputation paid off when he was named one of two drivers to represent the Duesenberg team in the European Grand Prix, an 800-kilometer, 496-mile race in Monza, Italy. American racing was coming into its own, and the Grand Prix circuit (today called Formula 1) had seized on the growing rivalry by announcing that it would encourage American entries to test their machines against the best the Europeans had developed.

Pete would soon learn that the captain of the Duesenberg team, Milton, was one of the strangest men ever to grasp a steering wheel. He was blind in one eye, and, to compensate, he had developed a habit of tilting his head back and shifting it quickly from left to right like a nervous sparrow. He never acknowledged his disability, and few had the nerve to ask him about it, but he adopted the odd physical strategy to ensure that his single eye could keep him fully informed about his surroundings.

Milton had learned his moves by racing on the county roads and dirt tracks of the Midwest, and that probably played a role in the selection of Pete, who had mastered his driving skills in a similar rural setting. Tommy was widely recognized as a hard charger, not only behind the wheel, but also in the garage, where he hovered over mechanics shouting instructions in rapid-fire staccato.

Seeing a great opportunity to trumpet the mechanical achievements of their cars internationally, the Duesenberg brothers immediately jumped at the opportunity by registering two drivers: veteran Tommy Milton would drive one of the Dueseys and Pete Kreis the other. Indy winner Peter De Paolo had decided to enter Monza in a home-grown Alfa-Romeo, a brand celebrating his Italian heritage.

Although some have described Milton as somber, intense is a more precise adjective, and he exhibited that defining quality throughout his life. In advanced age when poor health precluded his fulfilling a long-standing retirement job at Indianapolis Motor Speedway, he shot himself in the head to end his frustration. In 1925, Pete knew he could learn a lot from the veteran, and he eagerly joined the trip to Italy even though it would require missing a few races on the American circuit.

The men and their cars sailed to Genoa on the SS Colombo, the luxurious ocean liner that F. Scott Fitzgerald and his wife Zelda took to Italy a few years later. After docking, the race crew shipped the cars to Monza, northeast of Milan, which was the site of a royal park and summer retreat for the kings of Italy.

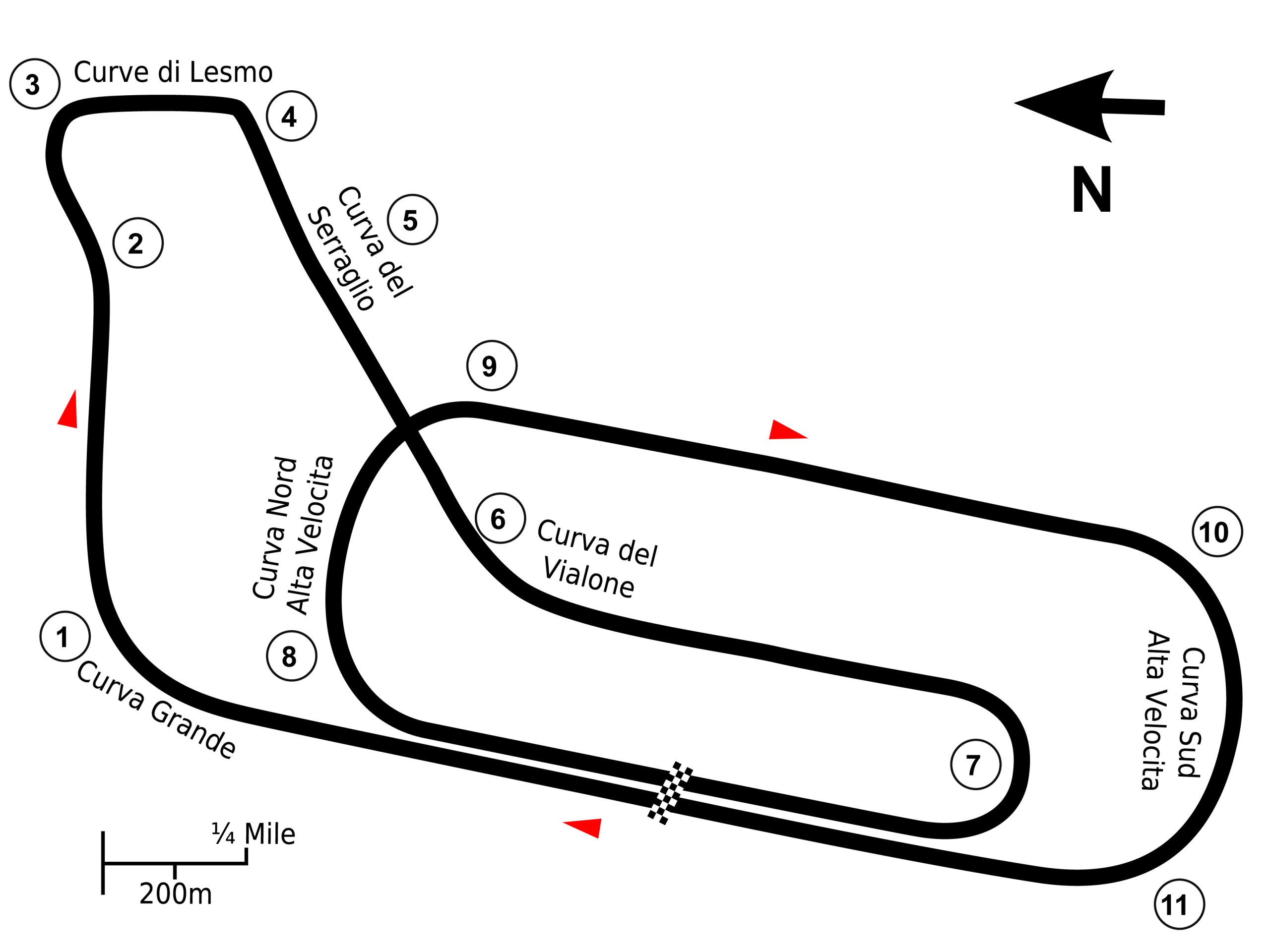

The Monza racecourse was set amid the park’s huge trees, gardens, fountains, and rolling hills. When the Americans arrived, they found that the track consisted of a road course and an oval, totaling six miles in length. Twisting like Italian spaghetti, the road course had ten curves, both right and left; some of them were complex with blind entries and double apexes. At one point, the track even passed over itself on a bridge. At the head of the home stretch was the notorious Parabolica, a right-hand, steeply banked curve. Like the turns on board tracks, the banking enabled cars to generate tremendous speed just before they were propelled down the home stretch, the longest on the course.

The third purpose-built track in the world after Brooklands in England and Indy, Monza was known to be a fast course, and drivers who had raced on it had a healthy respect—some might even say fear—of the facility. Living up to its reputation well into the modern era, the course has claimed the lives of fifty-two drivers and thirty-five spectators. In one of the worst accidents, Italian champion Emilio Materassi lost control of his roadster in 1928 and plowed through a flimsy barrier, killing himself and twenty-two spectators and injuring thirty more fans.3 As horrific as the accident was, it failed to dampen Italy’s enthusiasm for the sport, nor did the course’s reputation deter the Americans from giving it a try.

When they arrived, the Yanks quickly recognized that they weren’t in Indiana anymore. Italy was in the fervor of the Fascist revolution. Only three years before, Benito Mussolini—self-dubbed Il Duce, The Leader—had commanded his black-shirted Fascisti on the march to Rome, where they seized power. By 1925, the revolution was well established and growing stronger as Mussolini applied a powerful jolt to a country he perceived as an international sluggard. Throughout his career, Il Duce preached advancing—and even more so, accelerating. Sensing the worldwide spirit of the age, Italy placed a premium on speed.

But the Fascist revolution was more than a nationalistic political movement; it sought to infuse every facet of the nation’s life—even automobiles and racing. Mussolini loved powerful, speedy vehicles, and he purchased one of the fastest for his personal use, a two-seat Alfa-Romeo Type Two painted in the national tone, Italian racing red. Equipped with a supercharged straight-eight engine, the car could carry the dictator from Rome to his birthplace in northern Italy in record time.

The central role that racing played in Mussolini’s revolution was made clear in the wake of the Materassi accident at Monza, when one of the dictator’s ministers defended the sport from attacks by Catholic critics bemoaning the violence, carnage, and death. Party Secretary Augusto Turati declared that “Fascism has taught us that we need to live and win dangerously. The new Italy salutes its dead with pain, but from that pain we gain the strength to continue the battle to the summit.”

Using the prophetic rhetoric of the Italian poet Filippo Marinetti, the Fascists linked the growing cult of speed to the cult of death, a new alliance in which “living dangerously” on the track became a heroic act that encouraged other Italians to accelerate national progress. Those who died in the process became martyrs that energetic, determined citizens would emulate to advance Italy’s fortune. They were destined to become what Mussolini called “the new Fascist man.”

Il Duce wrote personal letters to Pete, Tommy Milton, and Peter De Paolo welcoming them to Italy and wishing them good luck at Monza; during practice, he visited the Americans in their garages. Following the dictator’s lead, scores of influential Italians journeyed to the track to examine the American cars, and Pete was photographed with King Victor Emmanuel, senior army officers, and many Fascist elite. As much as the Americans hoped to show the Europeans how their roadsters could perform, the Italians were sure their cars would put the entries from the United States in the shade with a swift surge of nationalistic pride.

As the Yanks sorted their cars out, they soon became the objects of scorn from their European competitors. Many of the jibes were aimed at the Americans’ lack of experience on road courses.

“What do you have to do to win Indy?” shouted one glib French driver. “Just get on the track and turn left . . . and turn left . . . and turn left . . . and turn left,” answered his compatriot, lampooning the Americans and their ubiquitous oval tracks. Such jokes were invariably accompanied by every European in the garage hoisting and twirling his index finger to mock the American “roundy-roundy” drivers.

The crowning blow was when another driver made a mock-heroic announcement that Pete’s last name, Kreis, was actually the German word for circle, something the American had never before heard. “Young Mr. Kreis is always going around in circles, getting nowhere,” shouted the rival driver with malicious irony.

A few days later, Kreis and his friends would have their revenge against the European tormentors, thanks to Kreis’s penchant for practical jokes. The culminating event was so hilarious that Peter De Paolo remembered it years later.

The drivers were scheduled to have dinner at a hotel located on a circular plaza in a nearby town. Pete had alerted his American friends to find parking away from the plaza, while the Continentals eagerly grabbed the reserved VIP spots surrounding the central fountain. As the Yanks entered the banquet hall a bit late, the European drivers welcomed them warmly with cheers and raucous shouts of “roundy roundy” emphasized by whirling index fingers—taunts aimed at the oval drivers from across the Atlantic.

After the laughter died down, the rivals enjoyed a feast of the finest Italian pasta, sauces, and wine. As the drivers shared their experiences and chatted about the upcoming race, no one noticed that Kreis had left the hall and returned inconspicuously sometime later. The conversation and drinking continued well past midnight even though the crews faced an early morning call for practice the next day.

As they finally finished and walked out of the hotel around one in the morning, the drivers found an amazing sight waiting for them. Dozens of taxis were clogging the plaza by driving around it bumper-to-bumper, with the hacks enthusiastically blowing their horns and waving their index fingers in “roundy-roundy” circles. The cars of the European drivers in reserved spaces were trapped by the noisy circular parade organized and paid for by Pete Kreis.

When the Europeans finally deduced that the Americans had organized the rolling blockade to delay their going to their beds, they looked across the plaza and saw the Americans doubled over in laughter. Pete, Tommy, Peter, and friends had taken their nationalistic revenge.

The Europeans were in for another surprise on September 6, race day in Monza. From what the Continentals had heard, the Americans knew how to race only on ovals; they supposedly had no experience on road courses. What the Europeans didn’t understand, however, was that most US drivers grew up in rural areas where they had learned to deal with backroads, narrow rural lanes that swerved left and right into irregular, bumpy curves. In this manner, the Americans had undergone the same kind of grueling training the Italians had earned on the demanding Mille Miglia, a thousand-mile race on public roads that began and ended in Rome.

During days of tuning and practice, the Yanks adapted quickly to the challenges of the Italian road course, and Pete had shown amazing speed around the circuit. Impressed Italian crowds soon cheered the young Tennessean as il valoroso corridore americano (the valorous American driver).

Pete and the rest of the Yanks, however, were up against Europe’s best drivers, among them Gaston Brilli-Peri and Giuseppe Campari, Grand Prix champions piloting brilliant red Alfa-Romeos, at that time the dominant marque on continental tracks. Descendant of a noble Florentine family, Brilli-Peri cut his teeth on motorcycle racing before switching to four wheels. He was an Italian favorite who ran the Grand Prix circuit for years before his death in a Libyan race in 1930.

Giuseppe Campari was also a national hero, having won many races in Italy and abroad, including two victories in the Mille Miglia, which attracted an astounding five million spectators along the way. Besides his racing ability, Campari was also adored by fans because of his enormous appetite for pasta—confirmed by a Pavarotti-sized stomach—as well as his Pavarotti-toned voice, which led to a second career as an opera singer. A master of the Italian passions for opera, eating, and racing, he died in a crash at Monza in 1933, the perfect final aria that enriched the national cult of death.

While the two Alfa drivers dominated the scene in pit lane, standing in the background was a young mechanic who later became world-famous for his ability to construct speedy cars. Enzo Ferrari had originally driven for the Alfa team, but the deaths of so many of his racing friends convinced him to join the safety of Alfa’s team of designers and mechanics. After Enzo founded his own company in 1947, his red Ferraris dominated the Formula 1 world for decades and fulfilled his fervent dream: “I want to build a car that’s faster than all of them, and then I want to die.” In the end, he built thousands of the fastest cars in the world, and when he died in 1988, his cars had won an unprecedented sixteen Formula 1 championships.

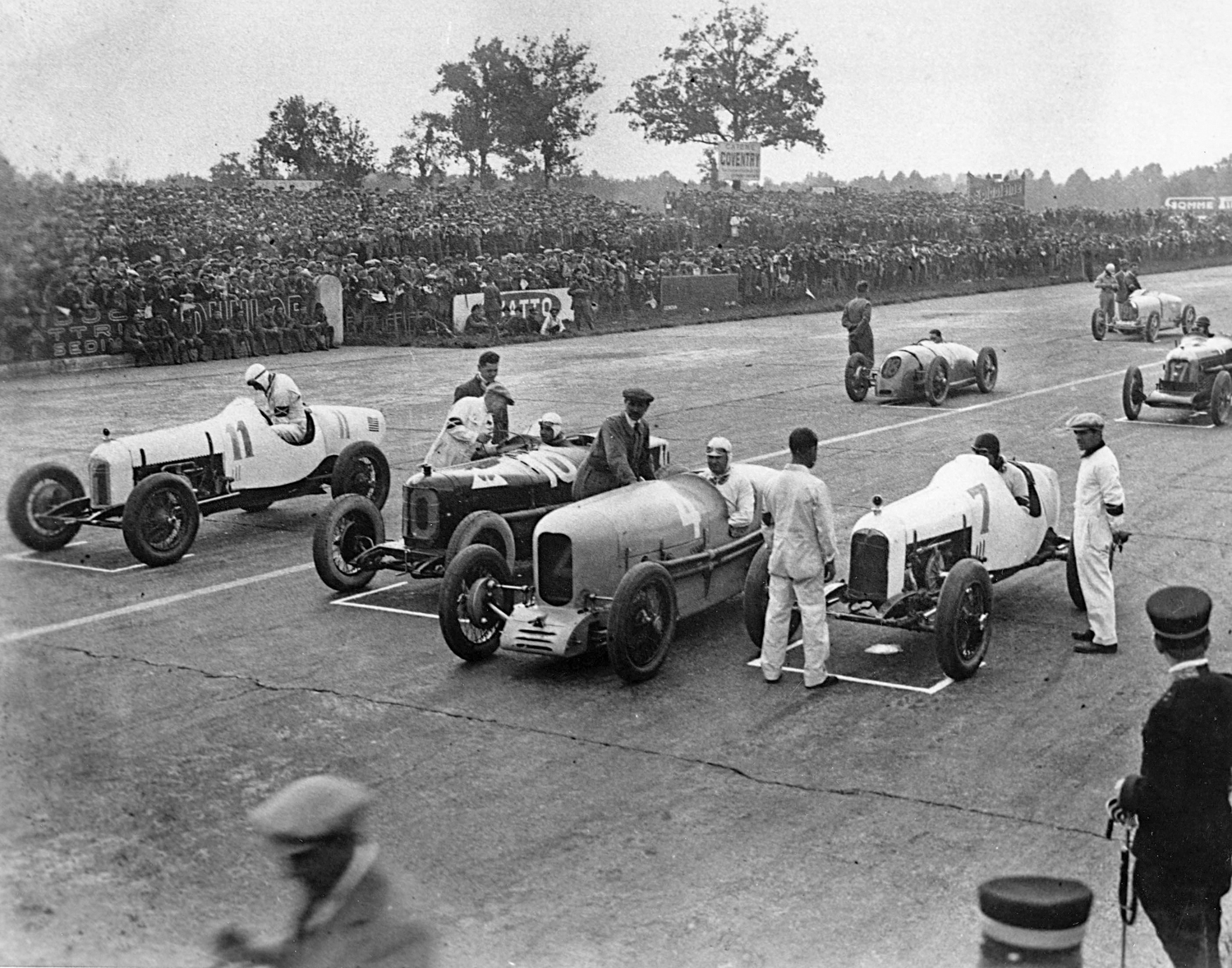

For obvious reasons, the national press billed the 1925 Monza Grand Prix an “Italo-American Duel,” a face-off between the two nationalities that attracted thousands of fans from all over Italy and around the globe. A British correspondent observed that “If the French are enthusiastic over motor racing, the Italians are delirious. Milan did not sleep the night before the Grand Prix . . . and the masses of spectators were quite satisfied to spend a few hours noisily and joyously in cafés and music halls, hotels and restaurants.”

Shortly after daybreak, a massive crowd of three hundred thousand fans began the twenty-mile trek from Milan on trains and buses to the track, dwarfing the 180,000 spectators who had attended the Indy 500 earlier that year. As the gates opened a short while later, drivers began assembling their roadsters on the starting grid, giving the fans a good chance to examine the cars that entered the race.

The differences in the designs of the teams’ cars were stark. Both featured roadsters with straight-eight-cylinder engines, but the Alfas contained a supercharger spinning at only 6,000 rpms, while that of the Duesenbergs revved to an astounding 27,000 rpms, forcing a much larger volume of powerful fuel-air mixture into the cylinders.

As it turned out, however, the most significant difference was not the engines, but the gearboxes. Designed for oval tracks, the American cars had three-speed transmissions because little shifting was required once the roadsters attained speed on the roundies. The Alfas, however, were developed for European road courses requiring many more shifts through the curves; as a result, the Italian cars had four-speed gearboxes of stronger design to accommodate the mechanical stress of frequent shifts. Because Monza was a course that required many shifts, Alfas had a built-in edge.

The American cars arrived at the starting grid sporting new livery: white bodies with blue numbers: Milton number 7, Kreis number 11—a not-so-subtle tip of the hat to the Goddess Fortune, who ruled the risky game of auto racing. Small American flags were emblazoned on the rear quarter panels of both machines in a nod to national pride.

The start was from standing positions, and the first to get away was the crowd favorite Campari, followed in order by Guyot, De Paolo, and Kreis. Poor Tommy Milton stalled his engine and got away last, angry steam rising from beneath his cloth helmet.

Campari had the lead when the pack passed the grandstands to finish the first lap, but on the second lap, Pete Kreis had planned a surprise to kick off the anticipated “Italo-American Duel.” When the fans expectantly looked to their right to catch the first glimpse of the cars coming out of the sweeping Parabolica curve at the head of the homestretch, they didn’t see the expected Alfa red, but the American white. Flying around the course, Pete had passed Campari and gone on to establish the fastest lap in the race—three minutes and thirty-five seconds.

This was Kreis at his absolute best, running the race he always envisioned: ahead of the pack, drifting curves with grace, and roaring down the homestretch of his dreams. Drivers often describe this unusual sensation as being “in the zone,” a space magically out of time and place in which racing is easy, effortless, and intuitive. All negative thoughts are vanquished.

“Suddenly I realized that I was no longer driving the car consciously,” Brazilian Formula 1 champion Ayrton Senna said of a similar experience years later. “I was driving it by a kind of instinct, only I was in a different dimension.”

Pete reached that mystical dimension right on time to bring Monza’s crowd to its feet, cheering his achievement. The Americans had likely planned to send Kreis out as a rabbit to tempt the Italians into some hot laps to test their mettle. Then, according to the scheme, Tommy would charge to the front when the forerunners backed off to save their engines. The strategy worked out perfectly, except for Milton’s stalled engine, a disadvantage that Tommy’s skill would soon erase.

As the crowd looked up the homestretch to see who was leading at the end of the third lap, however, they were amazed to see not Kreis in the lead, but Campari. They waited several tense moments, but when Milton’s white roadster appeared before Kreis’s, Italian racing aficionados concluded that Pete had suffered a breakdown or an accident.

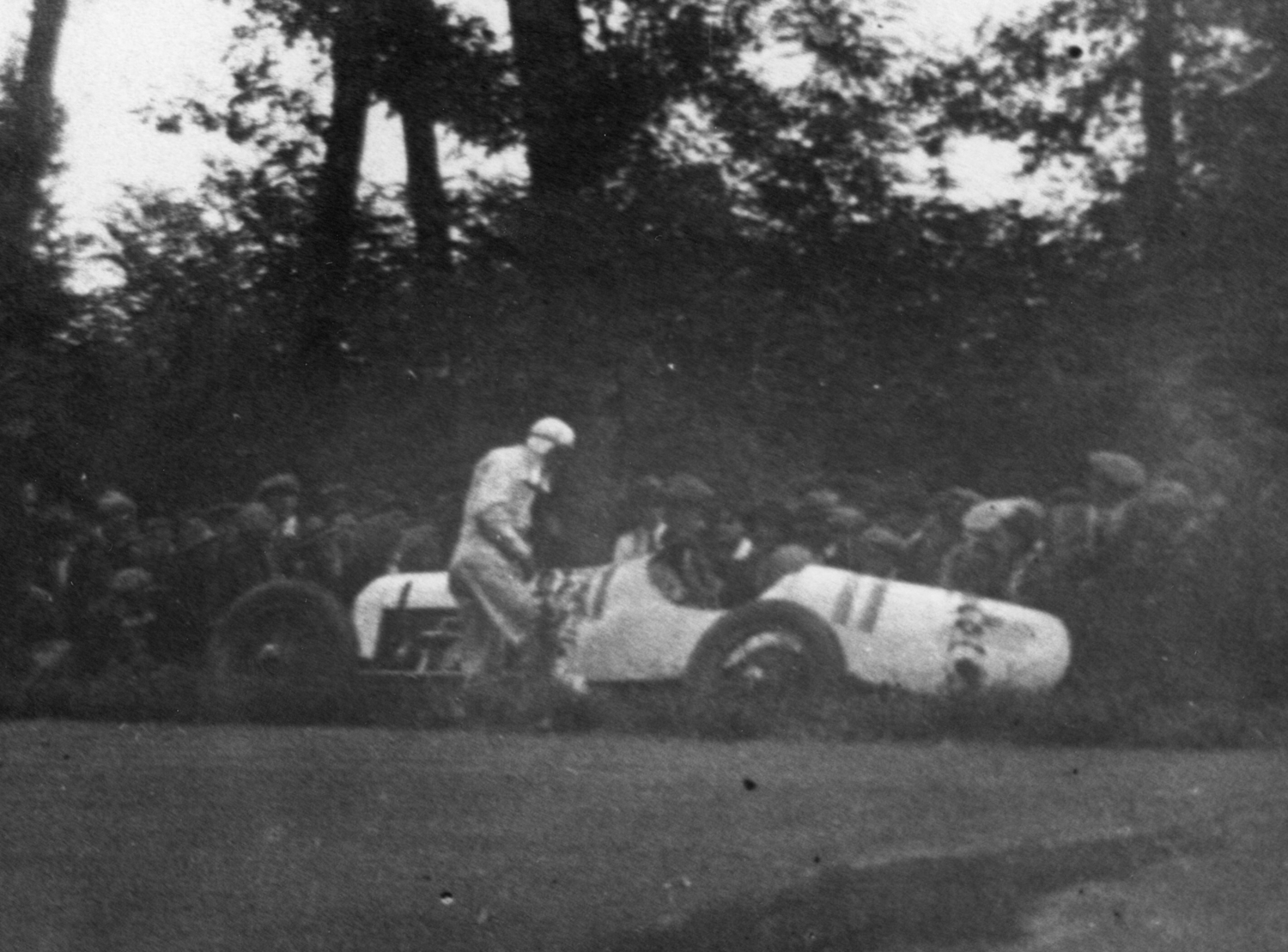

Kreis’s crash happened at Porto Lesmo, a blind, complex curve with dual apexes where he lost control in the first bend. Pete ended up broadside against a tree just off the racing surface; multiple spins had scrubbed off much of his speed so that there was virtually no damage to the Duesenberg. The American driver leapt from the car and put his shoulders to the wheel to push the roadster back on track, but it was wedged too tightly for him to budge it.

Noting his plight, enthusiastic spectators who loved the Americans broke down the restraining barrier and gleefully joined in moving the car back to the track. It was then that Pete envisioned the dreaded black flag in a racing official’s hand: it was forbidden for the drivers to receive assistance from spectators. Kreis would be disqualified. Before that action was taken, however, Pete managed to withdraw from the race, a move that ensured that his new lap record would be preserved for the time being. The crowd gave the American driver a huge ovation for his speed and sportsmanship as he walked back to the pits.

Track officials blamed the accident on excessive speed, but Pete clarified the matter later. Under the pressure of frequent shifts, the Duesenberg’s clutch had broken, and Kreis had entered the curve in neutral. When he tried to reengage the gear to negotiate the second apex, the gear seized and spun the car out of control. Meanwhile, Milton carried the American reputation into fourth place with Campari, Brilli Peri, and De Paolo leading the way. Soon, however, Milton’s Duesey passed De Paolo, and when the two other Alfas pitted for fuel and tires Tommy forged into the lead with an average speed of 96.7 miles per hour. Very shortly, however, things began to fall apart for the second American car, when Milton’s transmission stuck in third gear and slowed his acceleration coming out of turns for the duration of the race.

At the halfway mark, Milton pitted—and the time the stop required demonstrated the valuable experience of the Italian team. The Duesenberg crew took four minutes and fifty seconds to get Milton back on the track, while the Alfa team accomplished the same task in less than a minute and a half. The European cars once again took the lead, never again surrendering it. With only ten laps to go, Brilli Peri had a seven- and-a-half-minute lead over the second-place car and won by the same margin. Milton finished fourth, with De Paolo in fifth.

At the conclusion, fans poured onto the track and hoisted the hefty Brilli Peri, Campari, and the diminutive De Paolo on their shoulders and marched to the royal box where the trio was presented to Prince Umberto, the oldest son of the Italian king. Standing in front of the royal party, the huge crowd broke into an enthusiastic version of the Italian national anthem.

Amid the jingoistic fervor, European newspapers were quick to declare that the “Old World had beaten the New.” Even so, the Americans had raced well: Milton and De Paolo finished in the money, while Kreis had established the fastest lap. But given the steep learning curve and the logistical challenges the Americans faced, the Duesenberg team felt that they had represented their nation well, and they looked forward to another opportunity to test themselves against the Europeans—one that would come in 1927.

After a team celebration that extended well into the evening, Pete slipped away to downtown Monza where he located the local telegraph office. On a single white sheet, he scribbled a few words that profoundly confused the Italian telegraph operator but made immediate sense to the US recipient that Pete craved most to please.

“Broke track record and car. Love, Pete,” read the telegram that was delivered to the owner of Riverside Farm.